On

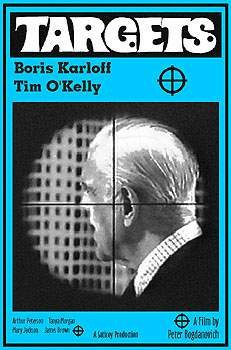

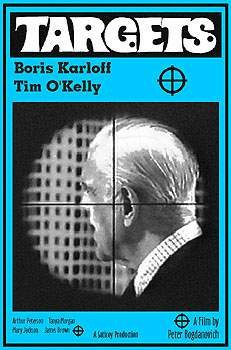

Targets

Very good film, doesn't really offer any attempts at answers though, stuff just happens. I guess that the number of scenes of him buying bullets with such ease could be construed as against the US gun culture but it doesn't offer of attempt any simple explanations.

[Okay, an extended response]

You mean it doesn't offer a CSI-style forensic "explanation"? You're right. Of course not, as such explanations would be mere lumpen-empirical deflections and displacements from the wider cultural context. Bogdanovich [or rather,

nouvelle vague hero Samuel Fuller and the sublime Orson Welles (see other thread

), the real powerhouses behind the film's extraordinary script, making it Bogdanovich's best movie, rare for a debut film] sets out to avoid such pat explanations, instead adopting the uneasy, uncanny perspective of the dispassionate gaze, as impersonal as a surveillance camera. As Marsha Tupitsyn recently observed, "The most discernable difference between

Taxi Driver and

Targets is that Bickle is a claustrophobic meditation on male isolationism and violence, while Targets, a much more inclusive film, is about endless links and parallels. It is indebted to and aware of the cultural framework of its cinematic narrative and the ways in which medial narratives forge new terrors. The terror that Bobby Thompson ensues is only one of many. In other words, it’s nothing personal, or messianic, as in the case of

Taxi Driver, and instead has everything to do with collective repression, the industry of exploitation, and the historical commission and representation of violence." This is why Bogdanovich avoided characterising the sniper-killer in psychological terms. He could have easily done so: Whitman's autopsy revealed that he had a brain tumor; he was also addicted to prescribed psychotropic drugs such as Valium, and had been discharged from the Marine Corp. But these "details" would have detracted from the wider aims of the narrative: Bogdanovich (or rather Fuller/Welles) chose to leave his character Bobby Thompson existential and elliptical in terms of motive, thereby making him more sinister and symptomatic of the "new" kind of horror. As Lawrence Russell elaborates, "In one way his actions can be seen as a protest against the incomprehensible rat-race of contemporary living, symbolized by the automobile on the freeway and in the Drive-In. His frustration seems driven in part by the fact that he has no job, is drifting... although there is no sense that this is an issue with his family. We get the impression that he's a child-man, and is regarded as such ... but the disease that Bobby carries is societal and historical. "

Indeed, the film is one of the very first examples [apart from Wilder's

Sunset Boulevard] of the postmodern condition, the real clue to this contemporary horror. It's singular deneument foreshadowed works by Lynch, Cronenberg, Kubrick [indeed, the film self-reflexively replaces the traditional-filmic Gothic romanticism and expressionism of darkness and shadow with the breezy 60's California documentary-naturalistic pastels of Pathe color, as Kubrick later did in

The Shining] and others, in its portrayal of the collapsing down of the imaginary and the real. In

Targets two horrors are colliding and overlapping, but more importantly, cinematic violence and real violence are expressed collaboratively. For this reason, the film is ahead of its time. In the end, when killer Bobby gets trapped between the screen Orlok-Karloff and the real Karloff-Orlok - who has revived his status as monster in order to confront his competition, like Godzilla in a match against King Kong - Bobby doesn’t know which one to fear, or resist, they're indistinguishable, the screen Karloff as hyper-real as the actual Karloff - so he shoots at both of them. As Karloff-Orlok marches at him from both sides, the effect is very powerful, for the film is an early evocation that there is little difference between the screen and the real, and in the psychic economy, very little space from it.

Tupitsyn concludes: "The film is a reflection on many things: the history of horror, the status of genre, but most boldly, it addresses the construct of monstrosity itself. What makes a monster a monster? How does something become monstrous? And, finally, in what ways is the culture invested in the maintenance of monstrosity, and by extension, perfection? In other words, the changing status of what society sees, or is willing to see, as horrific. Horror both follows and disrupts social conventions - as in the case of Dracula, a filter for the clichés and sexual anxieties of Victorian society. Or, a hundred years later, with the 1980s backlash against the feminist movement erupting in the Slasher genre’s revival of phallic supremacy. Not that it ever really went away. Equally, as Robin Wood points out in his famous definition [of horror: "“One might say that the true subject of the horror genre is the struggle for recognition of all that our civilization represses or oppresses"] , horror also ceases to follow conventions, thereby magnifying the unconscious power of horror even more. "