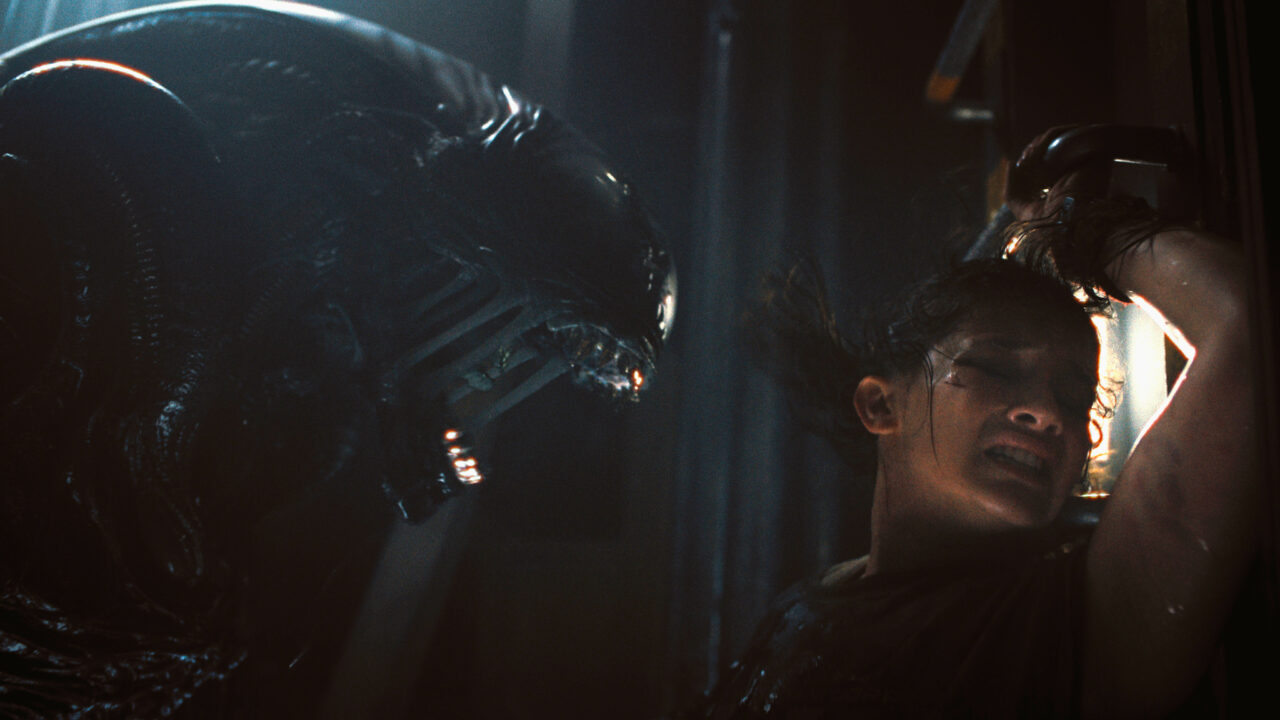

And part of the perfect organism? Is the capacity to work together. Just look at the Marines. Conflict and cooperation are not antagonistic concepts; they are inextricable, one in the service of the other. What brings warring families together is a new shared threat, a new enemy, a new Other. And the disappearance of this Other may—and often does, inevitable—bring with it new in-fighting, and intra-othering, another splitting of unity. Competition begets coordination. Violence begets peace. A packs of chimps assemble, drumming on treetrunks, signaling to males near that a hunt's begun. On all fours, walking through the underbrush, they spot red colobus monkeys in the treetops above. A few form a perimeter, the rest flush up, up. Scaling the walls, the towers, as if up ropes and ladders—up into the trees they climb, spotting their ideal victim, the infants they will try to separate from mothers, devour limb by limb. The attackers are spotted. The ambush begins; pandemonium breaks out. In the aftermath, the tender flesh of lamb and veal enjoyed with leafy greens, the chimps will share their meat among allies and mates, exemplars of generosity and kindness. This is the logic of power, and of connection. War, as Robert Wright’s Nonzero: The Logic of Human Destiny incessantly argues, is one of the great forces of cooperation. On Twitter, the libs are ooh’ing and ah’ing over nature’s mutualism, deriving hope from inter-species symbiosis. But every example? Is born of conflict. Badger and coyote, hunting together: one runs the prey into its burrow; the other, digging, flushes it out. Shrimp clean parasites from the moray’s mouth, as oxpecker’s clean buffalo teeth, and Egyptian plovers the incisors of crocodiles. Boxer crabs wield anemones like weapons. Ants tend to their host acacias, attacking any herbivores which threatens it. Ravens lead wolves to their prey; the wolves, destructuring tough hide, expose the entrails, left-overs for the birds.