version

Well-known member

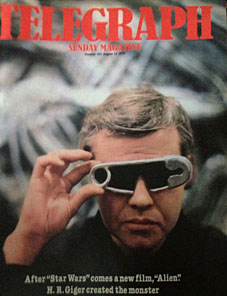

THE MAN WHO PAINTS MONSTERS IN THE NIGHT by Robin Stringer

The man in black is talking about his monster. “It is elegant, fast and terrible. It exists to destroy—and destroys to exist. Once seen it will never be forgotten. It will remain with people who have seen it, perhaps in their dreams or nightmares, for a long, long time. Perhaps for all time.”

The speaker is H. R. Giger, a Swiss-German surrealist painter, who designed the monster for Alien, the latest screen shocker, made in British studios under British direction to meet the apparently insatiable twin public cravings for space and horror films. Alien has already persuaded Americans to queue in record-breaking numbers outside their cinemas. It is said to have recouped its £15 million cost within 26 days of opening, and it comes to Britain on September 6.

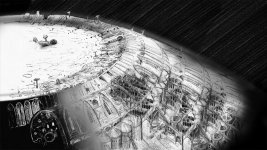

The crew of a space tug on a fuelfinding mission answer a distress signal from an unknown planet. They land and discover an alien spacecraft in which, unknown to them, an awful creature has been spawned and waits seething, but with infinite patience, for a chance of life. Taken on board the space tug, clinging to one of the crew, the creature parasitically reproduces itself in him and bursts out into life in a welter of blood. It proceeds to make itself at home on board by hiding in dark places and jumping out at passers-by. It gobbles up the space crew one by one and grows prodigiously. Being unfamiliar with the monster’s lifestyle, the crew understandably panic.

That in brief the story of Alien, which, of course, has actually been spawned by the movie makers to scare us just a little bit and, in the process. to make them a lot of money.

The man who designed the monster will make some money, too—though not a lot, he says. He is not on a percentage. H. R. Giger, who calls himself H.R., because “the other things are too long and complicated”, is a chunky 39-year-old who lives with his girlfriend/secretary Mia, two cats, 12 skeletons and some books on magic in the middle of a rickety row of terraced houses in the industrial outskirts of Zurich. He always wears black.

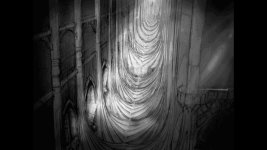

There, with airbrush, he paints his weird nightmarish paintings which blend the human form (usually a highly stylised naked woman) with machinery, reptiliana and bones. The pictures are often extensions of his nightmares.

Giger, on the other hand, is friendly, chatty and down to earth. “We mostly work at night,” he says, “so we have no ‘phone calls. I work while Mia reads to me from different books—from Dune, from Old Magicians, or from the novels of Gustav Meyrink, the romantic mystic who died in 1932. We work till three or four in the morning and sleep in late.

“I work in the way of the Surrealists. I sit before a white canvas and begin with an airbrush. I don’t know what will happen. I am curious to know. I often surprise myself.”

To those who complain that his paintings are frightening, ugly and emotionally cold, he replies: “People say many things about my pictures because they are unusual. I don’t like ugly things. I think my creatures are beautiful in another way. You measure everything by the human being. If you know them a little, you think differently. It’s always the new things you are frightened of.

“It’s also that I want to find out what’s in my body. It’s like an analysis, like going to a psychologist. It’s how you find out what you are occupied with what obsesses you. It’s a purifying process.

“As for warmth, visitors who come to our house never find it cold. There’s a harmony here.”

Eve Arnold, the photographer who visited Giger, vouched for the warmth of the welcome. “After the first day’s work between the witches and the skeletons, not to mention the black ceilings and the mind-provoking art, I was rather afraid I would have nightmares.

“Not so: it was all so friendly and pleasant that I began to enjoy my strange surroundings, to relish pizza by candlelit skulls and to appreciate my gentle hosts. The dining room housed a magnificent black table designed by Giger and a sculptured automaton, in the bowels of which were a large brass platter bearing some decaying apples (real) and a black cat (live). On the table there were black candles in a surreal candlestick also made by Giger. The ceiling was black and there were no windows. They had been boarded over, with huge murals which were everywhere in the tiny house.

“In the studio there were 12 skeletons. In addition to the real ones there was a lovely one in metal. There is a witches circle there, too, where the house witch lives. Mia, who was wearing a black & apron with a white skeleton painted on it, giggled and said they should try to enlist the witch’s help to get the people next door to move. Then they could buy the house and join the two together to give them more room.”

Giger plainly values his present relationship with Mia. “She works as my secretary and we work very close. We each need the other. I am very happy to have found Mia. This time it’s going much better with my mental state.” The couple have no children. “We have two cats, one Siamese and one black. They are like our children,” says Giger. “I want very much to keep my freedom and you have to care about children so much.”

Mia interrupts again. “He cares so much that he is very afraid to have a child. He thinks about the world.” “Maybe later,” rejoins Giger.