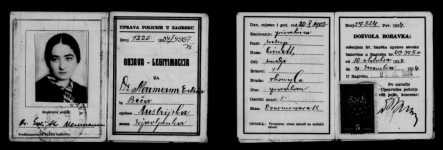

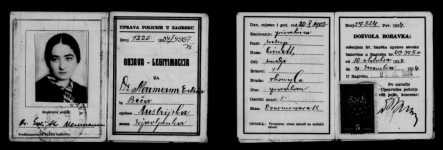

I found this 1000 page pdf of this woman's life on archive.org - documents and letters starting from 1905, she was born in vienna, converted from judaism to xtianity, had to flee anyway (she met Heidegger, hated him and he probably denounced her to the nazis), she ended up as a new yorker.

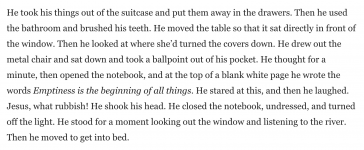

this bit i found really speaks to me, her own account of "Memories of our home at the beginning of the 20th Century." it's OCRed so forgive typos

Take it away Dr. Edith Neumann

Memories of our home at the beginning of the 20th Century.

To keep up our fairly small apartment and the family (2 adults, 2 children), 2 indoor

servants, cook and parlormaid who was also nanny, 1 helper (Bedienerin) three times a

week, for several hours (outside), 1 washerwoman once a month over a long day, and a

sewing woman in spring and fall every year for about two weeks each, were necessary.

The servants had low wages but they were quite satisfied and saved most of their money at

the bank (Postsparkasse). Many of them stayed for many years. At Christmas, they got

material for a new outfit; when they feil sick, the doctor came to look after them, and when

one of them got pregnant - which they managed though they were off (Ausgang) only every

other Sunday afternoon - my father saw to it that the responsible man (Verehrer) married

her.

A middle class American housewife would not understand why so many people, including

my mother, were necessary to keep up the household. It is best explained by enumerating

that which was not there. As there are few poeple left who still remember, I will set down

the facts. Thus the following will not be so much my biography but a description of

everyday life before 1914.

Most historians deal with war, politics, and economics, but very few of them had ever

known what to do with a dirty tablecloth or a worn out shirt cufT.

No indoor water. There was an outside tap shared with the neighbours next door.

In my parents* bed room was a large dresser of black marble. On it stood two large basins

of embossed procelaine painted with pink roses. To the set also belonged a pitcher to refiU

the basins, a pail for the dirty water, and on a narrow shelf two cups for water, a narrow

long Container for the toothbrushes and a Container for the toothpowder (no toothpaste

yet!) and, last but not least, the Chamber pots - everything with roses. We children had a

less elaborate set of hardier porcelaine with a blue pattern.

On a low bench (Wasserbankl) in the kitchen stood two large pails each with its own ladle,

one for working purposes and one for cleaning. Drinking water at meals had to be fresh

from the tap.

Above the tollet seat was a contraption which let some water down every time a cord was

puUed. It had to be refiUed several times a day.

I was still very young when my father made some very important improvements. He took

some part of the foyer and made a bathroom out of it with. A tall stove heated by gas gave

enough warm water for several baths in succession, and a pilot light delivered some warm

water during the day (if one was careful). Father also had a W.C. (Wasserklosett) installed.

No Electricitv. The rooms were lit with gas (Auerbach Struempfe) which were of a very

fragile material (asbestos?) and had to be replaced quite often. My parents had candles on

their tight tables. After a time, the most important chandeliers were electrified for their

middle lamps and electric lamps were put on the bedside tables (Nachtkastln).

No vacuum cleaners. Everything was done by broom and brush except that every now and

then the oriental rugs were taken to the court yard. There stood a long level wooden pole

held high up on both sides by vertical legs of the same material. The rugs, one after the

other, were thrown over it Usually two people worked it on both sides and beat the dust out

of it with a flat Instrument made of young bendable sprigs which were plaited in a pretty,

very loose pattem, got a handle and were dried to harden (Pracker). This was very good for

the rugs (probably better than the strong vacuum cleaners) but very bad for the girls in a

city füll of tuberculosis. Fortunately, they did not contract this desease.

Do detergents except fine, mostly French soaps for the employers (Herrschaft) and a hard

brown soap (Schichtenseife) for everybody and everything eise.

NoSOS or similar cleaners. Every month a man with a cart (Der Sandmann) brought sand

from the Danube to fill an old pot He also delivered several bunches of dried algae (called

Waschein).

No floor polisher. The floors were hardwood parquettry in a fishgrate pattern and were

polished by woman power. It was done with flat oblong brushes with very short, hard

bristles which were larger than a human foot and had their upper surface covered with a

black bumpy material (Linoleum). The worker stood barefood on one and steadied herseif

with a broom under which was a dustcloth. So she danced up and down each row of

diagonal wood Strips wiping after herseif with the dust cloth. My mother who was grace

personifled could do it with brushes under both feet. She encouraged us girls to do it often,

saying it made beautiful hips.

No washing machine. No drver. Washday was an event which everybody hated. In the

basement was the room for it (Waschkueche). In it were two long vats with tilted sides and a

plug to let the dirty water out into the drain (Waschtrog). The afternoon before, the

servants fiUed them with water and some lye, put the loundry/washing in and let it soak

until the morning. Early next morning the washerwoman (Waschfrau) came and started the

Are in the stove for heating the water in two large vals. In the meantime, she rinsed the

washing in fresh, cold water, put it back into the vals, poured hot water onto it and then the

work Started in earnest. She had a washboard (Kumpel). On it she soaped and rubbed

every piece of loundry, e.g. a sheet from one end to the other, not leaving out a spot Then

the whole thing was slightly rinsed, put into the vals on the stove with enough slivers of soap

and let it boil for some time. After that the loundry was again treated on the washboard

(gerumpelt!) and then rinsed in cold water. Usually, the parlormaid helped at that

procedure. After wringing out as much water as possible, the wet linen was taken in an

oblong basket with two handles (Waschkorb) to the attic and hung there to dry. This

needed 2 persons for the wet load was very heavy. It was taken down while still slightly

damp, the sheets were stretched by two people holding them on both sides. When I was

older I was one of them and found that puUing much fun. Then all flat-ware was taken to

the neighbouring milkshop (Milchfrau) where there was a big mangle to hire by the hour.

At one time most of the material was starched (I do not know when).

One of the extra task was supplying the washerwoman with food. Every two hours she got

a substantial meal accompanied by a bottle of beer. This had to be brought to her to the

badly lit basement on a tray. When I was older, it was occasionally my duty, and I hated it

(because of the roaches).

At last came the ironing. This was a dangerous procedure. The untensil had about the same

form as a modern iron but it was hoUow. It had a flap at the back to close. The heat was

delivered by a piece of cast iron (slightly smaller) with a hole on one end. It was put into the

hot coals in the stove and left there until it was glowing red. Then it was taken out by a long

hook (Schuerhaken) and fitted into the hoUow outer form. This procedure could easily

cause injuries. The iron was, of course, terribly hot and one had to take great care not to

burn the linen. But it cooled gradually and the ironer knew which pieces to take according

to the temperature. When it was too cold, the inside iron was taken out, replaced by a

second hot one from the stove and the cold one put again into the stove.

Np Nylpn. No synthetic material like Nylon, Acetate, existed at that time, therefore NO drip

dry, NO colorfast materials. Therefore, all delicate material had to be washed by band

separately by the parlormaid, hung to dry under the ceiling in the kitchen and very

carefuUy ironed.

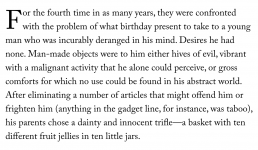

The Kitchgn. NO canned or frozen food, except French Sardines in olive oil and small

Italien tins with tomatoe paste.

NO Mixer. NO Blender. NO Cuisinar. Everything was woman power. All flat surfaces,

mcluding the large board (Nudelbrett) on which all dough for noodles and any dessert that

was kneaded and flattened to desired thinness with a roUer (Nudelwalker) were of a

beautiful pale, hardgrained wood (maple?). All other wooden implements were of the same

material. Every Saturday, they had to be rubbed clean with sand and soap. The flat

surfaces were covered after the midday meal with table cloths embroidered in blue cross

stich by my sister and me).

As there was NO refrigeration. my mother went Shopping daily. Nothing was in cartons or

packaged in Standard weight (Kilogramm, Dekagramm). The groceries were put into paper

bags, the vegetables usually in newspaper and also the meat Only the butter got

parchment The vegetables, especially the root vegetables, needed thorough cleaning

because they came just as the farmer had brought them. Chicken had to have their left

over feathers bumed off and all the entrails had to be taken out very carefuUy in order not

to tear the gall-bladder. It would make the whole meat bitter. Everything purreed had to be

pressed throuhg a hair sieve (NO blender) and the famous Viennese tortes, e. g. Sachertorte,

had to be stirred - always in one direction - for half an hour. Heavy cream and egg white

was beaten in a half globe kettle of brass (Schneekessel) with a wire Instrument

(Schneerute).