You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Eagle vs The Serpent

- Thread starter luka

- Start date

jenks

thread death

It’s the symbol associated most with the Hapsburgs. Remember it as a key symbol in Joseph Roth’s Radetsky March.Isn't the eagle often with two heads, a kind of Romanov related symbol?

jenks

thread death

And didn’t he show off by doing it twice when signing his name?I think it was Giotto whose submission to gain entry to the academy or whatever was a perfect circle drawn by hand.

jenks

thread death

And this on the symbol of two snakes wrapped around a pole, known as a caduceus,

mcdreeamiemusings.com

mcdreeamiemusings.com

Two snakes or one? How we get the symbol for Medicine wrong — mcdreeamie-musings

Healthcare is full of antiquity, not surprising for a venture as old as humanity itself. Humans have always got sick and always turned to wise men and women and the divine to help them. With that comes symbols and provenance. Wound Man. The Red Cross. The Rod of Asclepius. Ah yes, the Rod of Asclep

sus

Moderator

...did you read the entry or just the synopsis, you knucklehead

Coat of arms of Mexico - Wikipedia

en.m.wikipedia.org

Says right there it was adopted in 68

In 1968, President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz ordered a small change, so the eagle would look more aggressive.

Guys, I think Pattycakes is losing it. Not mentally fit enough for this board, low bar as that may be. We may need to intervene

pattycakes

Well-known member

...did you read the entry or just the synopsis, you knucklehead

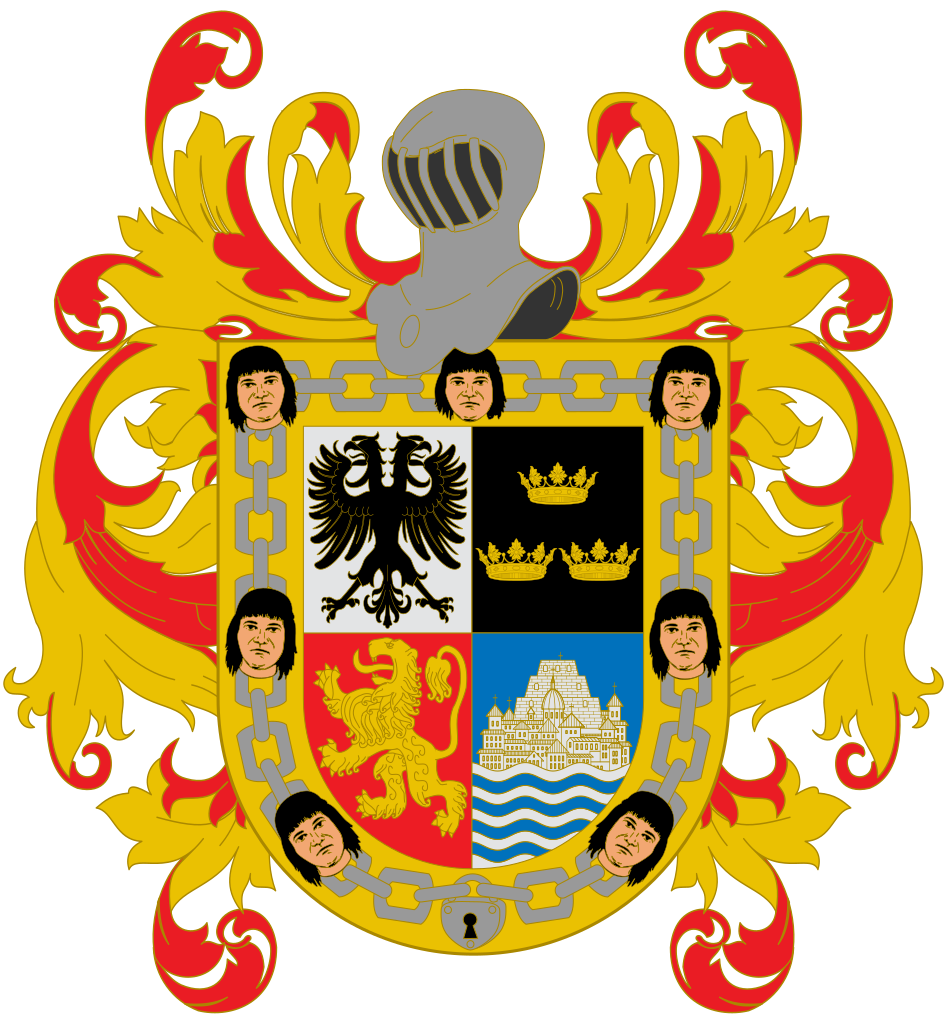

View attachment 6294

Guys, I think Pattycakes is losing it. Not mentally fit enough for this board, low bar as that may be. We may need to intervene

From the same wiki

Moreover, the original meanings of the symbols were different in numerous ways. The eagle was a representation of the sun god Huitzilopochtli, who was very important, as the Mexicas referred to themselves as the "People of the Sun". The cactus (Opuntia ficus-indica), full of its fruits, called nōchtli in Nahuatl, represents the island of Tenochtitlan. To the Mexicas, the snake represented wisdom, and it had strong connotations with the god Quetzalcoatl. The story of the snake was derived from an incorrect translation of the Crónica Mexicáyotl by Fernando Alvarado Tezozómoc.[citation needed] In the story, the Nahuatl text ihuan cohuatl izomocayan "the snake hisses" was mistranslated as "the snake is torn". Based on this, Father Diego Durán reinterpreted the legend so that the eagle represents all that is good and right, while the snake represents evil and sin. Despite its inaccuracy, the new legend was adopted because it conformed with European heraldic tradition. To the Europeans, it would represent the struggle between good and evil. Although this interpretation does not conform to pre-Columbian traditions, it was an element that could be used by the first missionaries for the purposes of evangelism and the conversion of the native peoples.[2]

so basically no one can really say what the original meaning was because like so many of these things the europeans stuck their religious oars in and stirred it to suit their own needs. p.s. there may have been no snake in the OG flag to start with *shrug*

so neither of us know the real story. but for me, my hunch is based on the eagle having long been appropriated by the white man as the symbol of control and dominance, and as you can see here by 1525, a few years after the Spanish arrived in Mexico and Hernán Cortés made this the new coat of arms:

ye olde double headed eagle es en la casa. which predates your 200 years by quite some time.

but you're right, i did get it mixed up on the previous page.

however, i still stand by the symbolism of it all, and the updated version in 68 coinciding with the hippy awakening era. because ultimately i think all of this stuff revolves around the war against the psychedelic awareness (aka eleusian* freedom) that the usuran eagle headed overseers are so strongly against the masses attaining.

* @Mr. Tea didn't you promise us a thread on this a while back? feels relevant because eagle/serpent feels very eleusis/usura

Last edited:

IdleRich

IdleRich

Wasn't there something - I could be misremembering this - but the Aztecs believed in the symbol of the eagle and serpent (as stated above) and when Cortez or whoever it was turned up there was some occurrence that recalled that and as a result they thought that maybe he was the god returning, and it was that hesitation in attacking and pulverising the invaders which allowed them to gain a foothold and started a chain of events which ended with the Spanish conquering the natives.

Mr. Tea

Let's Talk About Ceps

I remember reading somewhere, possible in The Golden Bough, about how well the conquered Aztecs/Mexica took to Christianity, because the idea of a god who sacrifices himself in order to be reborn and thereby renew the world was already familiar from their own religion.When I went round chichenitza, we got talking to an old tour guide and he said the Christians used the native Mexican veneration of serpents as a way of justifying their subjugation, cos of negative the connotion of snakes within Christianity.