mvuent

Void Dweller

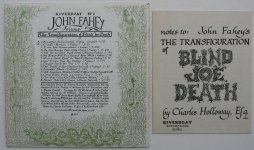

fahey was a super early adopter of the parodic, pseudo-authoritative liner note. but the ones that have stuck in my mind are the hilarious and eerie creative writing exercises. dunno if you'd call them mise en scene but they certainly set a very specific and fitting atmosphere.

A disgusting, degenerate, insipid young folklorist from the Croat & Isaiah Nettles Foundation for Ethnological Research meandered mesmerically midst marble mansions in Mattapan, Massachusetts. It was an unsavory, vapid day in the summer of 2010 as the jejune air from Back Bay transubstantiated itself autologically and gradually into an ozone-like atmosphere.

Knocking on a random door, haphazardly, the tasteless young man pondered the Hebraic inscription on the marble-tiled foot-brush, soporifically: "I wonder what the hell that means," he said to himself reflexively. The foot-brush backed itself into a corner at bay, with its back to the wall. Then, hissing at the wishy-washy young man, it reared up on its hind leg & stared into space, vociferously & stolicly. At this juncture a somewhat equivocal shoe-shine man opened the door, munching on a vacant popsicle stick. Before greeting the young man he reached up with a tentacle and stroked the aging foot brush on its fore, thus quieting the beast's existential anxiety.

"Pardon me," the unflavored young man said casually, "Do you have any old arms and legs you'd like to sell? I'm paying thirty-seven, twenty-five, ninety-six, twelve cents apiece for old arms & legs depending on the condition they're in."

"Just one moment," the splotched ontology professor mumbled, "I think we may have a few out back in the quagmire, or possibly near the fen, or then again we may have some by the waters of the boggy bayou. I must point out, however, that it is quite possible that we have none left. And I should also say that we may never have had any anyway. I certainly can't remember ever having any. (...)

There is a pulp-mill somewhere in Maryland. And this mill pours its refuse into what is now, but was not always a land-locked lake. And in that lake lived an enormous turtle, (only one) very old, very large, his shell painted by moss and pulp. You can (or at least I can) hear his voice, or rather cry, sometimes late at night when everything else is still. He was there long before the mill came. The water is bad now, but there are still a few carp and cat-fish on the bottom for him to snap up and chomp on. For some reason no one else has ever seen him, and as an amateur herpetologist I should like to say that he resembles no species that I have ever seen or heard of elsewhere. There he spends his days confined to the polluted water. There is no outlet. He cannot make it to the sea. Nothing ever gets out of that lake. (...)

Now, yet surer of himself, he proceeded back through the viaduct toward the magic place where Carroll Avenue is majestically transubstantiated into Laurell Avenue. Stopping to inspect his aufheben, bruised when he tripped over the street artist, he saw a familiar form approaching from the mystic corner, Domenick Zurubian, his boyhood friend and idol! He stood stiffly waiting by the glass front of Youngblood's hardware store not daring to hope that Domenick Zurubian would rec ognize him; it was as well so, since Domenick Zurubian ignored him with a vaguely hostile glance, and began to pass by.

"Wait" he called to stop him, the words tore from his aufheben almost against his will. "Here is your pencil."

A light began to glow in Domenick Zurubian's oblique eyes (yes, those fascinating angled eyes, in the form of a horizon tal seven). "Don't I know you from somewhere?" "Yes, yes, the fourth form in the Takoma Military Academy!" "Well, damn if I can remember who you are," said Zurubian, with out embarrassment. "There were a couple of ambivalent indeterminate young men in that class." Zurubian left him by the glass front of Youngblood's hardware store with a lame excuse, and a smile, softly and resolutely, crisping his lip.

"Yes, then: I am an ambivalent indeterminate young man." His voice was a warm human bourgeois whisper, as he resolutely dissolved into the fog with the sound of drying wild flowers. "The wolves," he said, looking out the door before the stranger came in, "are gone now." (...)

Emerging into the sun, he began to cross the gentle rolling hill of new mown hay when suddenly from out of nowhere a herd of wild dogs attacked him and tore his clothing and his limbs. Their teeth bit into his flesh. Screaming and bleeding he ran towards a farm house which he made out on a distant slope. Arriving there breathless he ran up the steps onto the porch. Throwing open the door he ran into the dwelling and slammed the door shut behind him. An old farmer who was seated in an oversized wicker basket jumped up at this and demanded of the resolute young man resolutely:

"What is this doggerel? Who do you think you are, running into my dwelling here in the midst of time?"

"Sir," he said, "I am beseiged by a herd of wild dogs. They have ripped and torn my clothes and I am bleeding profusely."

"I can see that you are bleeding and that your clothes are torn, but come look out the window. There are no dogs out there, and there never have been, not on my farm. What you saw was only some pages of old newspapers blowing in the wind. Come and see," said the old farmer. The young man turned towards the window and looking out of it he saw that there were indeed no dogs, now. Only old newspapers being tossed about on the sunny slopes of new moan hay. Strange though, they had the appearance as they blew to and fro of those very dogs which had just now attacked him. (...)

Last edited: