You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Baader-Meinhof Film

- Thread starter IdleRich

- Start date

version

Well-known member

‘05 Spielberg terrorism movie, added to top of the list

One of his best. Spielberg attempting a 70s political thriller. Also perhaps his harshest film. There's one scene in particular that's ice cold.

version

Well-known member

Love Munich, apart from the final scene which as I recall is hilarious

Yeah, serious fumble there. Sex scene epiphanies, have they ever worked?

version

Well-known member

This guy was on the run for 49 years and just turned himself in on his deathbed about a month ago:

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

Satoshi Kirishima - Wikipedia

The Red Terror that Continues to Haunt Germany

Few things capture the public imagination like a nationwide hunt for high-profile criminals. For weeks, many Germans have been hooked on the detailed reports in the media about the capture of Daniela Klette. The 65-year-old woman was arrested in late February 2024 and now stands accused of...

version

Well-known member

Christopher Hitchens on The Baader Meinhof Complex

Movies have often romanticized Communist revolutionaries—think Benicio Del Toro as Che. But a new action thriller, The Baader Meinhof Complex, counterpunches, exposing the violent psychosis that gripped the young militants of the Red Army Faction in 1970s West Germany.

dilbert1

Well-known member

Christopher Hitchens on The Baader Meinhof Complex

Movies have often romanticized Communist revolutionaries—think Benicio Del Toro as Che. But a new action thriller, The Baader Meinhof Complex, counterpunches, exposing the violent psychosis that gripped the young militants of the Red Army Faction in 1970s West Germany.www.vanityfair.com

His point about the most violent groups being in formerly Axis countries (even though Germany’s the obvious one) hadn’t occurred to me! I still feel as though that past is so murky that its neither here nor there whether the Stammhein deaths were suicides, since either way the brunt of the critique rings true. As much as I’m critical of the New Left, I don’t share his pure outright antipathy for even the worst of its expressions. Its a nasty and morally ambiguous history, and while their acts of terrorism aren’t noble in my eyes, I still feel its not my place to completely dismiss them as straightforwardly bad actors, I see them more like confused fore-comrades and the historical cards they were dealt weren’t ideal, etc. Borderline apologist, Hitchens might say, but then again I agree with nearly all of his points here.

version

Well-known member

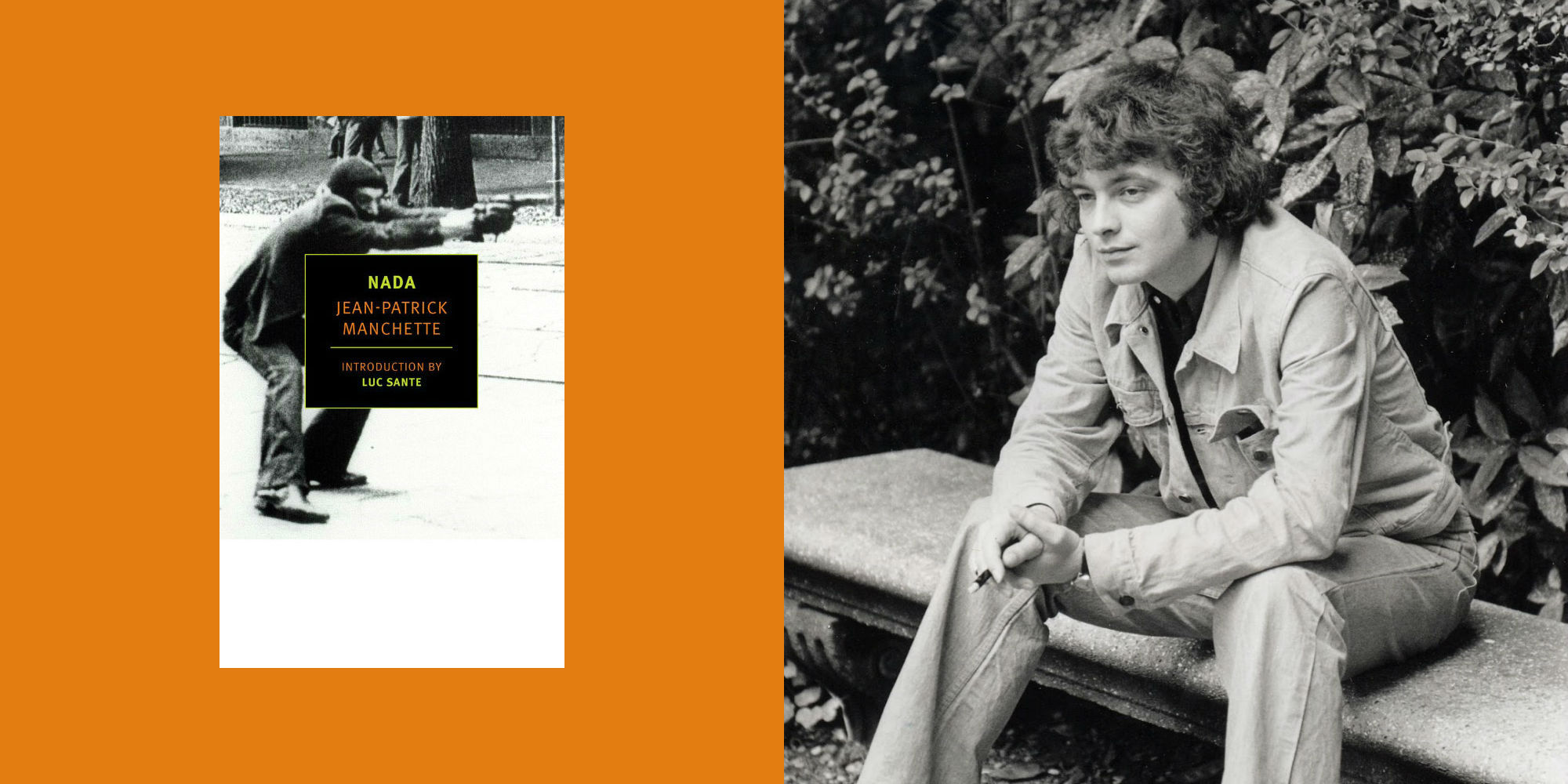

Have you read that Manchette novel I was on about earlier, Nada? That quote above is from the intro to my edition and is his response to his wife suggesting the characters might be positive role models. You can read the full intro online.

crimereads.com

crimereads.com

How Jean-Patrick Manchette Revolutionized the Left-Wing Thriller

Nada, first published in November 1972, was the fourth novel by Jean-Patrick Manchette, not counting pseudonymous titles, novelizations of films, and other products of what he called “industrial” w…

The book is briskly paced, full of clipped dialogue and nonstop action, but it also presents a political argument. Treuffais, who seems to be something of an authorial proxy, decides not to go along with the plot, for doctrinal reasons: “Terrorism is only justified when revolutionaries have no other means of expressing themselves and when the masses support them.” By the end, Diaz, who had kicked Treuffais out of his apartment when the teacher begged off, has come to agree with him. “Leftist terrorism and State terrorism, even if their motivations cannot be compared, are the two jaws of . . . the same mug’s game,” he admits. “The desperado is a commodity.” Manchette has the press dub the gang’s hideout “the tragic farmhouse”—the epithet used by the newspapers in 1912 to refer to the death scene of Jules Bonnot, the driver and press-appointed leader of the Bonnot Gang, an earlier model of that commodity. Sixteen years after its French publication, in his preface to the book’s first Spanish edition, Manchette acknowledged that its political argument was “insouciant and obsolete,” because it “isolated” the gang from the broader oppositional social movement, and furthermore failed to account for the “direct manipulation” to which the State would have subjected such a group.

dilbert1

Well-known member

Have you read that Manchette novel I was on about earlier, Nada? That quote above is from the intro to my edition and is his response to his wife suggesting the characters might be positive role models. You can read the full intro online.

No, I did read the interview with him you posted, though. Interesting stuff, the way he aspired at inhabiting a popular, “low” form of mass art in a subversive way as opposed to practicing contemporary art I found admirable. He seemed isolated and of a troubled conscience having been so impressed by Debord’s writings but from a distance, trying to make his work “critical” in that way like a difficult self-imposed balancing act. Labelling himself a “pro-situ” (well-known semi-slur amongst official members) must have been consciously self-deprecating. That kind of figure seems obsolete today for sure. Apparently some of his work was adapted to the screen, I wonder if to any great effect? Can hardly imagine his approval of the results, if only out of a reflexive obstinance.

version

Well-known member

Started this last night.

letterboxd.com

letterboxd.com

For the UK people, the full series (six episodes) is on Channel 4's streaming service at the moment.

Exterior Night (2022)

The 1978 kidnapping and murder of Aldo Moro by the Red Brigades as seen by an outsider perspective, that of his family and political allies.

For the UK people, the full series (six episodes) is on Channel 4's streaming service at the moment.

version

Well-known member

Because in the US I can’t watch stuff on Channel 4 and am annoyed I’d have to figure out using a VPN which also I hear has become more difficult lately @version

It might be on a US streaming service too, or one of the illegal ones.

Interesting it's the third time the director's made something about the Moro kidnapping. He did Good Morning, Night and a documentary on it too.

version

Well-known member

Is it any good?

I enjoyed the first episode, yeah. That one's on Moro himself then the following episodes focus on the Minister of the Interior, the Pope, the Red Brigades and Moro's wife, respectively. The last one's on the end of the whole thing.