You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Etymology

- Thread starter luka

- Start date

luka

Well-known member

Fluent’ comes from Latin fluere to flow, which also gave the Latin word for river, flumen.30 ‘River’ is Anglo-Norman, with less clear origins in Latin riparia, riverbank, but it is ultimately derived from an Indo-European word meaning ‘to cut’ (‘rift’ is a cognate).31 Rivers are obviously ‘fluent’ – but they also cut through land and demarcate boundaries, and there is no etymological flow from ‘fluent’ to ‘river’. Many river names are ancient, surviving through periods of wholesale linguistic change; ‘Severn’ and ‘Thames’, for example, are among the very few remnants of a long extinct British (or perhaps even pre-Celtic) language.32 In ‘guard[ing] its name’ (if indeed ‘it’ is the river), the river refuses to be fully ‘fluent’. The ‘fixed

decision’ – perhaps a human settlement on the riverbank – that is ‘no less fluent’ than the river is therefore also subject to this deconstruction of the concepts of flow and rift.

The etymology of ‘river’ is more audible in its cognate ‘rival’, a word that appears four times in this short poem.33 ‘Rivals’ lived on opposite banks of a river, cut off from but bound to each other. This neutral meaning of something like ‘stranger’ seems to be more relevant to Prynne’s use of the word: ‘the rival comes, with clay on his shoes’; ‘the rival / ventures his life in deep water’; ‘some generous lightness which we / give to the rival when he comes in’. But this neutrality is difficult to accept, since it has been wholly replaced by the modern sense of competition and antagonism. One must have a motive for crossing rivers and deserts of snow, and the semantic development of ‘rival’ seems to show that aggression is the default interpretation. For example, the poem quotes John of Plano Carpini, the Pope’s ambassador to the Great Khan in 1246–1247 (the relevant river here is the Volga) who would perhaps have put the Holy Roman Empire in grave danger had the letter he carried not been mistranslated, leading the Mongols to believe that the Church had surrendered.34 This indicates how distance charges relationships between people, binding their fates even whilst it separates them. In the poem’s final few lines, this is made clear when, in place of the definite article attached to all the other rivals, a possessive pronoun is used:

[...] The wanderer with his

thick staff: who cares whether he’s an illiterate scrounger—he is our only rival. Without this the divine family is a simple mockery [...] (71)

30 ‘Fluent, adj. and n.’, OED; ‘Bhleu-’, IEL.

31 ‘River, n.1’, OED; ‘1. Rei-’, IEL.

32 Eilert Ekwall, English River-Names (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1928), p. xxxv. For a more recent account, see P. R. Kitson, ‘British and European River-Names’, Transactions of the Philological Society, 94.2 (1995), 73–118.

decision’ – perhaps a human settlement on the riverbank – that is ‘no less fluent’ than the river is therefore also subject to this deconstruction of the concepts of flow and rift.

The etymology of ‘river’ is more audible in its cognate ‘rival’, a word that appears four times in this short poem.33 ‘Rivals’ lived on opposite banks of a river, cut off from but bound to each other. This neutral meaning of something like ‘stranger’ seems to be more relevant to Prynne’s use of the word: ‘the rival comes, with clay on his shoes’; ‘the rival / ventures his life in deep water’; ‘some generous lightness which we / give to the rival when he comes in’. But this neutrality is difficult to accept, since it has been wholly replaced by the modern sense of competition and antagonism. One must have a motive for crossing rivers and deserts of snow, and the semantic development of ‘rival’ seems to show that aggression is the default interpretation. For example, the poem quotes John of Plano Carpini, the Pope’s ambassador to the Great Khan in 1246–1247 (the relevant river here is the Volga) who would perhaps have put the Holy Roman Empire in grave danger had the letter he carried not been mistranslated, leading the Mongols to believe that the Church had surrendered.34 This indicates how distance charges relationships between people, binding their fates even whilst it separates them. In the poem’s final few lines, this is made clear when, in place of the definite article attached to all the other rivals, a possessive pronoun is used:

[...] The wanderer with his

thick staff: who cares whether he’s an illiterate scrounger—he is our only rival. Without this the divine family is a simple mockery [...] (71)

30 ‘Fluent, adj. and n.’, OED; ‘Bhleu-’, IEL.

31 ‘River, n.1’, OED; ‘1. Rei-’, IEL.

32 Eilert Ekwall, English River-Names (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1928), p. xxxv. For a more recent account, see P. R. Kitson, ‘British and European River-Names’, Transactions of the Philological Society, 94.2 (1995), 73–118.

sufi

lala

"Calque" itself is a loanword from the French noun calque ("tracing; imitation; close copy").[1] Proving that a word is a calque sometimes requires more documentation than does an untranslated loanword because, in some cases, a similar phrase might have arisen in both languages independently. This is less likely to be the case when the grammar of the proposed calque is quite different from that of the borrowing language, or when the calque contains less obvious imagery.

Calquing is distinct from phono-semantic matching.[2] While calquing includes semantic translation, it does not consist of phonetic matching (i.e., retaining the approximate sound of the borrowed word through matching it with a similar-sounding pre-existing word or morpheme in the target language).

My new etymological term/concept of the week https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Calque

Luscious examples dripping with sweet and sticky etymological word-syrup

One system classifies calques into five groups:[3]

- phraseological calques, in which idiomatic phrases are translated word for word. For example, "it goes without saying" calques the French ça va sans dire.[4]

- syntactic calques, in which syntactic functions or constructions of the source language are imitated in the target language, in violation of their meaning. For example, in Spanish the legal term for "to find guilty" is properly declarar culpable ("to declare guilty"). Informal usage, however, is shifting to encontrar culpable: a syntactic mapping of "to find" without a semantic correspondence in Spanish of "find" to mean "determine as true."[5]

- loan-translations, in which words are translated morpheme by morpheme or component by component into another language. The two morphemes of the Swedish word tonåring calque each part of the English "teenager": femton "fifteen" and åring "year-old" (as in the phrase tolv-åring "twelve-year-old").

- semantic calques, also known as semantic loans, in which additional meanings of the source word are transferred to the word with the same primary meaning in the target language. As described below, the "computer mouse" was named in English for its resemblance to the animal; many other languages have extended their own native word for "mouse" to include the computer mouse.

- morphological calques, in which the inflection of a word is transferred.

This terminology is not universal. Some authors call a morphological calque a "morpheme-by-morpheme translation".[6] Other linguists refer to a phonological calque, in which the pronunciation of a word is imitated in the other language;[7] for example, the English word "radar" becomes the similar-sounding Chinese word 雷达 (pinyin "léi dá").[citation needed]

Loan blend

Loan blends or partial calques translate some parts of a compound but not others.[8] For example, the name of the Irish digital television service "Saorview" is a partial calque of that of the UK service "Freeview", translating the first half of the word from English to Irish but leaving the second half unchanged. Other examples include "liverwurst" (< German Leberwurst) and "apple strudel" (< German Apfelstrudel).[citation needed]

luka

Well-known member

luscious - Wiktionary, the free dictionary

luka

Well-known member

From earlier lushious, lussyouse (“luscious, richly sweet, delicious”), a corruption of *lustious, from lusty (“pleasant, delicious”) + -ous. Shakespeare uses both lush (short for lushious) and lusty in the same sense: "How lush and lusty the grass looks" (The Tempestii. I.52).

An alternative etymology connects luscious to a Middle English term: lucius, an alteration of licious, believed to be a shortening of delicious.

An alternative etymology connects luscious to a Middle English term: lucius, an alteration of licious, believed to be a shortening of delicious.

luka

Well-known member

There's a lot of secret etymological history to be dug out i reckon - decolonising the disctionary is overdue

What are you suggesting has been concealed?

sufi

lala

Arabic and islamic origins of words and indeed knowledge has been deliberately and systematically concealed by bigotted word-smths for centuries, dear LuciusWhat are you suggesting has been concealed?

constant escape

winter withered, warm

I'm sure a great dirty deal has been concealed, intentionally or not. Regardless, I love this thread. Favorites that come to mind now are "matrix" (cognate with "maternal", womb as space of creation) and "robot" which goes as follows"

1923, from English translation of 1920 play "R.U.R." ("Rossum's Universal Robots"), by Karel Capek (1890-1938), from Czech robotnik "forced worker," from robota "forced labor, compulsory service, drudgery," from robotiti "to work, drudge," from an Old Czech source akin to Old Church Slavonic rabota "servitude," from rabu "slave," from Old Slavic *orbu-, from PIE *orbh- "pass from one status to another" (see orphan). The Slavic word thus is a cousin to German Arbeit "work" (Old High German arabeit). According to Rawson the word was popularized by Karel Capek's play, "but was coined by his brother Josef (the two often collaborated), who used it initially in a short story."

Murphy

cat malogen

Fluent’ comes from Latin fluere to flow, which also gave the Latin word for river, flumen.30 ‘River’ is Anglo-Norman, with less clear origins in Latin riparia, riverbank, but it is ultimately derived from an Indo-European word meaning ‘to cut’ (‘rift’ is a cognate).31 Rivers are obviously ‘fluent’ – but they also cut through land and demarcate boundaries, and there is no etymological flow from ‘fluent’ to ‘river’. Many river names are ancient, surviving through periods of wholesale linguistic change; ‘Severn’ and ‘Thames’, for example, are among the very few remnants of a long extinct British (or perhaps even pre-Celtic) language.32 In ‘guard[ing] its name’ (if indeed ‘it’ is the river), the river refuses to be fully ‘fluent’. The ‘fixed

decision’ – perhaps a human settlement on the riverbank – that is ‘no less fluent’ than the river is therefore also subject to this deconstruction of the concepts of flow and rift.

The etymology of ‘river’ is more audible in its cognate ‘rival’, a word that appears four times in this short poem.33 ‘Rivals’ lived on opposite banks of a river, cut off from but bound to each other. This neutral meaning of something like ‘stranger’ seems to be more relevant to Prynne’s use of the word: ‘the rival comes, with clay on his shoes’; ‘the rival / ventures his life in deep water’; ‘some generous lightness which we / give to the rival when he comes in’. But this neutrality is difficult to accept, since it has been wholly replaced by the modern sense of competition and antagonism. One must have a motive for crossing rivers and deserts of snow, and the semantic development of ‘rival’ seems to show that aggression is the default interpretation. For example, the poem quotes John of Plano Carpini, the Pope’s ambassador to the Great Khan in 1246–1247 (the relevant river here is the Volga) who would perhaps have put the Holy Roman Empire in grave danger had the letter he carried not been mistranslated, leading the Mongols to believe that the Church had surrendered.34 This indicates how distance charges relationships between people, binding their fates even whilst it separates them. In the poem’s final few lines, this is made clear when, in place of the definite article attached to all the other rivals, a possessive pronoun is used:

[...] The wanderer with his

thick staff: who cares whether he’s an illiterate scrounger—he is our only rival. Without this the divine family is a simple mockery [...] (71)

30 ‘Fluent, adj. and n.’, OED; ‘Bhleu-’, IEL.

31 ‘River, n.1’, OED; ‘1. Rei-’, IEL.

32 Eilert Ekwall, English River-Names (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1928), p. xxxv. For a more recent account, see P. R. Kitson, ‘British and European River-Names’, Transactions of the Philological Society, 94.2 (1995), 73–118.

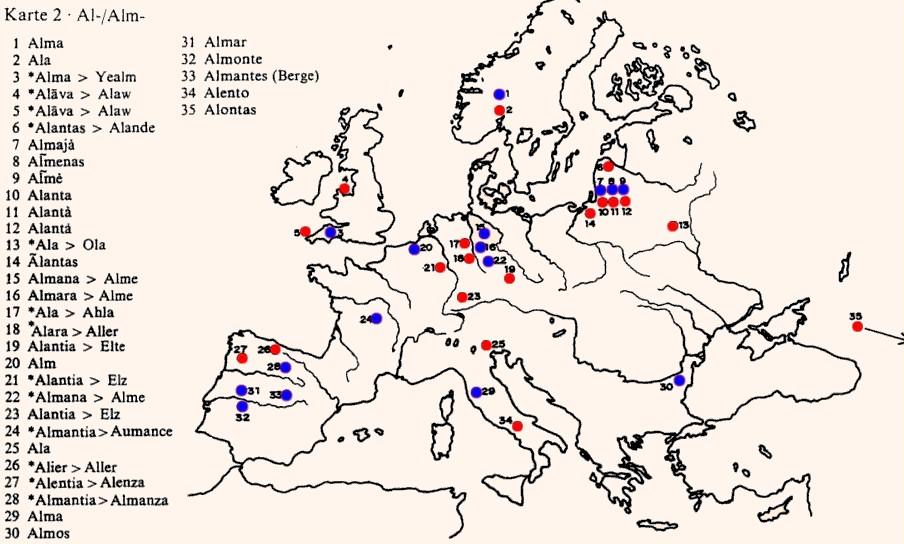

Side-note. There’s a world of river studies in hydronymy about trying to pinpoint the river names of Britain and Ireland to pre Indo European languages. The Clyde, Severn/Sabrina....

Old European hydronymy - Wikipedia

luka

Well-known member

Prynne rhapsodised about Pokorny to Charles Olson. "It sits on my shelf like an unexploded bomb."

"in the section given to KAR- for instance, with a root signification of hard or rough, he (Pokorny) shows an astonishing range of derived cognates embracing European words for 'rock' 'crab' 'shell' 'peel' 'nut' strong, bold, heavy, difficult, firm' perhaps also 'cliff, crag, crevice'

'stone, scarp' 'cairn, burial-mound, temple'...I have always felt this deep drive at the heart of North European languages, this reservoir of

latent energy never quite fully discharged even by the most direct of sentence constructions"

1961

Murphy

cat malogen

Macushla/acushla/cuisle in Gaelic means darling, but equates to pulse or vein.

Cwtch in Welsh means cuddle. “Give us a cwtch”.

From different people and familial influences, I’ve ‘heard‘ the two as similar (if not quite the same) phonetically. Cariad would be more exact, but as terms of affection they appear on similar linguistic wavelengths.

Cwtch in Welsh means cuddle. “Give us a cwtch”.

From different people and familial influences, I’ve ‘heard‘ the two as similar (if not quite the same) phonetically. Cariad would be more exact, but as terms of affection they appear on similar linguistic wavelengths.

sufi

lala

"in the section given to KAR- for instance, with a root signification of hard or rough, he (Pokorny) shows an astonishing range of derived cognates embracing European words for 'rock' 'crab' 'shell' 'peel' 'nut' strong, bold, heavy, difficult, firm' perhaps also 'cliff, crag, crevice'

'stone, scarp' 'cairn, burial-mound, temple'...I have always felt this deep drive at the heart of North European languages, this reservoir of

latent energy never quite fully discharged even by the most direct of sentence constructions"

1961

kar-3, redupl. karkar-

indogermanisch.org

see how he neglected anatolian 😱