You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

what are you reading now?

What if there was a contrarian black hole where a contradiction contradicted itself and became non-contradictory and so the universe exploded?not really

jenks

thread death

Beasts of England - Adam Biles. It’s a sequel to Animal Farm. He’s got the tone of Orwell right but at the moment (80 pages in) I am wondering what the point of the book is. Rather than Russia, Manor Farm is Britain and there’s clearly a Brexit theme in there. It rattles along quickly but at present I’m not entirely convinced.

mixed_biscuits

_________________________

"Saying that there is femininity in a man is like saying there is catness in a dog. One might wonder how did those bits of cat get in there in the first place." - Judith ButlerUpon finishing The Idiot, I can confirm, Prince Myshkin is a male lesbian. He is innocent, unassuming, and benevolent to a world that shuns him. His personality is a testament to the good will of people, good will that other do not reciprocate for him. There is femininity in a man with the resilience to remain meek in the face of constant tragedy.

Well that's not a real quote!"Saying that there is femininity in a man is like saying there is catness in a dog. One might wonder how did those bits of cat get in there in the first place." - Judith Butler

mixed_biscuits

_________________________

She is right neverthelessWell that's not a real quote!

william_kent

Well-known member

She is right nevertheless

the lack of turgid prose was a giveaway

but made me laugh, so full marks

version

Well-known member

William Harrison Ainsworth: "Auriol; or The Elixor Of Life" (1844)

I'm not expecting the world from a Victorian gothic pot boiler, and I get that it's probably hard to wrap up a plot that involves an immortal/time-travelling anti-hero and dwarf from 1599 getting mixed up with the Illuminati, four phantom brides and an East End dognapper in 1830s London - but fuck you, Ainsworth, for using "but it was all a dream!" to bring this novella to a grinding halt. This may well be the first book to feature an electric chair, though...about 45 years before one was first used for a real-life execution.

I'm not expecting the world from a Victorian gothic pot boiler, and I get that it's probably hard to wrap up a plot that involves an immortal/time-travelling anti-hero and dwarf from 1599 getting mixed up with the Illuminati, four phantom brides and an East End dognapper in 1830s London - but fuck you, Ainsworth, for using "but it was all a dream!" to bring this novella to a grinding halt. This may well be the first book to feature an electric chair, though...about 45 years before one was first used for a real-life execution.

dilbert1

Well-known member

Amazon product ASIN 1509542760

The Disappearance of Rituals by Byung-Chul Han, 2020

Just finished this book. While full of fascinating insight and useful conceptual clarifications, they culminate one-sidedly in a deeply and unmistakably conservative argument.

Han, in discussing Hegel’s master/slave dialectic, dispenses with the dialectic altogether and unequivocally praises the master. Kojève’s cartoonish post-historical Japan is uncritically championed as the highest, most ideal form of society. A la Bataille, nostalgia for archaic societies’ “strong” and glorious forms of play (festivals, elaborate politeness, but also blood rites, traditional warfare, and even suicide) is the simple corollary to Han’s dismissive contempt for modernity’s “weak” ones (mass entertainment events, social media, but also the very conception of play found in Kantian aesthetics).

Modernity, capitalism, Enlightenment, will-to-knowledge and will-to-truth, the compulsions toward authenticity and production, the centrality of work and survival, narcissism, the dislocation of religion and the sacred, and neoliberalism… These are all lumped in together as a vague, lamentable force which “desecrates life,” as Han is keen on repeating. Approving references to Agamben aside, deliberation on the critical potentialities of this desecration, of desacralization or “profanation” as Agamben terms it, is entirely absent. Well here we are, Han! Now what?

Yes, sovereignty as human freedom from necessity, the amoral character of beauty, the quality of play as an index of social flourishing (even if Han is silent around the precise nature of this indexical quality)… all valuable wonderful fascinating relevant things! Georg Simmel approaches some of Han’s same dilemmas in his essay on sociability. But although both authors elide from their analyses the dimension of political economy, at least Simmel wrestles with the very real possibility (tendency?) that a highly developed cultural commitment to semblance and formalism, to an “excess of the signifier,” can also mask enormous social decay and discontent… in other words, that the neutral and ‘unreal’ freedom of forms is but cold comfort to real social and political unfreedom.

Han hamfistedly registers the crisis of the debasement of ritual and play in wistful reverence for pre-modern social life without making space for such considerations. Sometimes Han’s vision for a new society of ritual sounds like socialism, but his simplistic contempt for modernity and the absence of politics in his argument signal otherwise. In fact, this ‘vision’ sounds much more like vain pontification and less a historical possibility or project.

All in all, a weakly argued entry into a fascinating and thought-provoking subject. Had the author been more willing to get his hands dirty rather than clutch his pearls, it might’ve been otherwise. Nostalgia for the bourgeois autonomy of art, while perhaps barely if at all more tenable, is preferable to such base primitivism. Han’s is a romantic anti-capitalism, and thus merely an expression of the very capitalist decadence he so derides.

The Disappearance of Rituals by Byung-Chul Han, 2020

Just finished this book. While full of fascinating insight and useful conceptual clarifications, they culminate one-sidedly in a deeply and unmistakably conservative argument.

Han, in discussing Hegel’s master/slave dialectic, dispenses with the dialectic altogether and unequivocally praises the master. Kojève’s cartoonish post-historical Japan is uncritically championed as the highest, most ideal form of society. A la Bataille, nostalgia for archaic societies’ “strong” and glorious forms of play (festivals, elaborate politeness, but also blood rites, traditional warfare, and even suicide) is the simple corollary to Han’s dismissive contempt for modernity’s “weak” ones (mass entertainment events, social media, but also the very conception of play found in Kantian aesthetics).

Modernity, capitalism, Enlightenment, will-to-knowledge and will-to-truth, the compulsions toward authenticity and production, the centrality of work and survival, narcissism, the dislocation of religion and the sacred, and neoliberalism… These are all lumped in together as a vague, lamentable force which “desecrates life,” as Han is keen on repeating. Approving references to Agamben aside, deliberation on the critical potentialities of this desecration, of desacralization or “profanation” as Agamben terms it, is entirely absent. Well here we are, Han! Now what?

Yes, sovereignty as human freedom from necessity, the amoral character of beauty, the quality of play as an index of social flourishing (even if Han is silent around the precise nature of this indexical quality)… all valuable wonderful fascinating relevant things! Georg Simmel approaches some of Han’s same dilemmas in his essay on sociability. But although both authors elide from their analyses the dimension of political economy, at least Simmel wrestles with the very real possibility (tendency?) that a highly developed cultural commitment to semblance and formalism, to an “excess of the signifier,” can also mask enormous social decay and discontent… in other words, that the neutral and ‘unreal’ freedom of forms is but cold comfort to real social and political unfreedom.

Han hamfistedly registers the crisis of the debasement of ritual and play in wistful reverence for pre-modern social life without making space for such considerations. Sometimes Han’s vision for a new society of ritual sounds like socialism, but his simplistic contempt for modernity and the absence of politics in his argument signal otherwise. In fact, this ‘vision’ sounds much more like vain pontification and less a historical possibility or project.

All in all, a weakly argued entry into a fascinating and thought-provoking subject. Had the author been more willing to get his hands dirty rather than clutch his pearls, it might’ve been otherwise. Nostalgia for the bourgeois autonomy of art, while perhaps barely if at all more tenable, is preferable to such base primitivism. Han’s is a romantic anti-capitalism, and thus merely an expression of the very capitalist decadence he so derides.

dilbert1

Well-known member

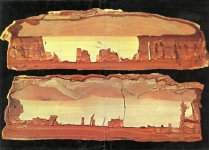

Roger Caillois, The Writing of Stones

Short thing discussing the patterns and images found in various minerals and their impact on the human imagination. It's out of print, but you can get the PDF on Monoskop.

View attachment 15986

version

Well-known member

@version is it good? Sounds trippy.

He gets really excited describing the stones and it gets better the further he moves into these surrealist descriptions.

Someone I spoke with said he sounded like Ballard, and I think they're right. This passage in particular comes off like a scene from The Crystal World:

"Occasionally they open out into ravines lined with little crystals. They form patterns which explode; showers of manysided cells; sprays of dodecahedra all on one plane; irregular veins branching out in all directions then suddenly tapering away; steelyards weighing a large object which is yet so light that the arm of the balance is unmoved; cobwebs spun in the void, attached to no point and containing no lurking spider; cross sections of murexes, with the helix in the middle and the spines on the outside; the waving tentacles of sea anemones; the filaments of jellyfish, ending in a whiplash. Out of the dark of the stone, between the beams of an incandescent star, shine bright streaks and points like dandelion seeds blown from the stem, fixed in their flight and forming a kind of halo around their original center."

A few descriptive bursts:

" ... in its night of polished jade it imprisons, sparkling brighter than its own somber surface, the crystals of a frost instinct with darkness."

"... panoplies of swords or fans of scimitars, twining them into coiling and uncoiling reptiles."

" ... decorated snakes with gaping jaws as in Aztec fables; pale caterpillars swollen with lymph and latex and eaten up with gangrene; the sinuous, maze like seams of the skull ... "

This is particularly visceral:

"We have here a universe of scrolls, branches, pleura; from them flayed countenances emerge, muscles laid open in their cavities of bone. There are lopped-off breasts, the mutilation twisting the raspberry nipples aside; there are the bodies of frogs, crucified by the galvanic current, their limbs splayed out by the shock, their skin turned blue and flabby by the violence of the spasm. Elsewhere we find a loose array of small tools, toys, and useful objects: bobbins, spools, shuttles, tops, drawer knobs. In the distance, but still quite near, are dunes, stretches of sand rhythmically modulated by the wind, a screen of hills, a host of weathered peaks with the geological strata bared, fleecy rowers as still as tropical clouds. The stone may be purplish blue, lilac colored; yellow turning green; the complete range of a bruise. It may be like a swollen sea of thick, almost solid bubbles, resembling an upsurge of sinister seaweed or an eruption of boils or buboes on an infected skin."

version

Well-known member

One of the things he says, and which immediately stuck, is that nature generates forms with no regard for representation yet here are natural examples of just that, meanwhile art began with representation before moving into abstraction.

In reality, it's not that clear cut, but it immediately made sense to me and I was with him.

He also makes the point that we can describe appreciation of art and natural phenomena with a shared vocabulary, i.e. beauty, but that this blurs the distinction between art and aesthetics and conflates two very different things.

In reality, it's not that clear cut, but it immediately made sense to me and I was with him.

He also makes the point that we can describe appreciation of art and natural phenomena with a shared vocabulary, i.e. beauty, but that this blurs the distinction between art and aesthetics and conflates two very different things.

IdleRich

IdleRich

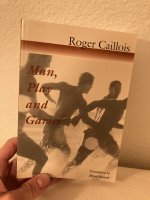

@version is it good? Sounds trippy. I’m about to crack into this Caillois after finishing the Rituals book. I’ll make @IdleRich proud by reading it in public without fretting over its vivacious title/cover combo

View attachment 16040

What's that? Oh you think it sounds gay and will thus rightly terrify any real red-blooded man who might be considering reading it... but thst hardly matters cos no man would ever consider reading... well any book really, with the possible exception of a quick re-read of Bravo Two Zero perhaps, cos men don't think about doing or read about other men doing, we just fucking do. Bish bash bosh done! Now on to the next thing. And if it's wrong one of my women can sort it out.

version

Well-known member

This one struck me as looking like some sort of Arabic script when I was looking around for a copy online.

@sufi

I wanted him to go a bit deeper into the idea of this stuff actually being writing, but he just says something poetic about trying to untangle the lines of a language that's folded in on itself then moves on.

It's that kind of book though. It's not aiming to be anything particularly rigorous. Imagine one of those Barty threads where he'd conjure fantastical imagery out of drill and dancehall. It's Barty if he were into rocks and minerals.

@sufi

I wanted him to go a bit deeper into the idea of this stuff actually being writing, but he just says something poetic about trying to untangle the lines of a language that's folded in on itself then moves on.

It's that kind of book though. It's not aiming to be anything particularly rigorous. Imagine one of those Barty threads where he'd conjure fantastical imagery out of drill and dancehall. It's Barty if he were into rocks and minerals.

mind_philip

saw the light

Sex and Rage by Eve Babitz. Mostly autobiography I think. She seems to have had a lot of fun, lucky thing. "Luck is like beauty or diamond earrings: people who have it cannot simply stay home."

IdleRich

IdleRich

I've read about EM Forster's short story The Machine Stops numerous times as an incredibly prescient prediction of a futuristic society in which everyone effectively lived the life of a bedroom-dwelling internet addict.

I'd always meant to get round to reading it one day but never quite had done. Then recently I was picking a new book to read by rooting around in my shelves - and I was pleasantly surprised to discover a book of EM Forster's short stories which contained that very one. I wonder how long I've had it unawares... good job I didn't order a copy at least I guess.

Anyway this book is really knackered, the front cover is missing and as I read the first story each page fell out after I turned it, it's a kind of one-shot book, destroy after reading, or by reading even.

After I'd read the first story I couldn't handle it any more, we never really tdlj about how the condition of the book, and even the shape, size, font, text size etc affect one's reading, but this just sat by my bed for ages until I decided to skip the second story and use that as a kind of buffer between the bit I'm reading and annihilation.

Anyhow, I read the next few stories and then got to The Machine Stops the first page of which is startling. It reads like a cruel piss-take of am online music critic that could have been written... right now, probably tomorrow even. It begins with a grossly fat woman on her chair listening to music that surrounds her from no visible source, then becoming irritated as one of her thousands of contacts interrupts her - it actually says "in certain directions human intercourse had advanced enormously". It's not just very accurate, it blows my mind, the first page ends with "I can give you fully five minutes, Kuno. Then I must deliver my lecture on "The lasting effect of Burial on the dubstep scene in UK and beyond".

Gibson's Neuromancer which came some sixty years later was praised for anticipating the internet, but this is truly uncanny. Well, so far, my train journey ended at that point, the rest of it will have to wait until tomorrow.

I'd always meant to get round to reading it one day but never quite had done. Then recently I was picking a new book to read by rooting around in my shelves - and I was pleasantly surprised to discover a book of EM Forster's short stories which contained that very one. I wonder how long I've had it unawares... good job I didn't order a copy at least I guess.

Anyway this book is really knackered, the front cover is missing and as I read the first story each page fell out after I turned it, it's a kind of one-shot book, destroy after reading, or by reading even.

After I'd read the first story I couldn't handle it any more, we never really tdlj about how the condition of the book, and even the shape, size, font, text size etc affect one's reading, but this just sat by my bed for ages until I decided to skip the second story and use that as a kind of buffer between the bit I'm reading and annihilation.

Anyhow, I read the next few stories and then got to The Machine Stops the first page of which is startling. It reads like a cruel piss-take of am online music critic that could have been written... right now, probably tomorrow even. It begins with a grossly fat woman on her chair listening to music that surrounds her from no visible source, then becoming irritated as one of her thousands of contacts interrupts her - it actually says "in certain directions human intercourse had advanced enormously". It's not just very accurate, it blows my mind, the first page ends with "I can give you fully five minutes, Kuno. Then I must deliver my lecture on "The lasting effect of Burial on the dubstep scene in UK and beyond".

Gibson's Neuromancer which came some sixty years later was praised for anticipating the internet, but this is truly uncanny. Well, so far, my train journey ended at that point, the rest of it will have to wait until tomorrow.

mixed_biscuits

_________________________

Disposable books - a great idea. Print with ink that fades within 5 minutes of exposure to the light.I've read about EM Forster's short story The Machine Stops numerous times as an incredibly prescient prediction of a futuristic society in which everyone effectively lived the life of a bedroom-dwelling internet addict.

I'd always meant to get round to reading it one day but never quite had done. Then recently I was picking a new book to read by rooting around in my shelves - and I was pleasantly surprised to discover a book of EM Forster's short stories which contained that very one. I wonder how long I've had it unawares... good job I didn't order a copy at least I guess.

Anyway this book is really knackered, the front cover is missing and as I read the first story each page fell out after I turned it, it's a kind of one-shot book, destroy after reading, or by reading even.

After I'd read the first story I couldn't handle it any more, we never really tdlj about how the condition of the book, and even the shape, size, font, text size etc affect one's reading, but this just sat by my bed for ages until I decided to skip the second story and use that as a kind of buffer between the bit I'm reading and annihilation.

Anyhow, I read the next few stories and then got to The Machine Stops the first page of which is startling. It reads like a cruel piss-take of am online music critic that could have been written... right now, probably tomorrow even. It begins with a grossly fat woman on her chair listening to music that surrounds her from no visible source, then becoming irritated as one of her thousands of contacts interrupts her - it actually says "in certain directions human intercourse had advanced enormously". It's not just very accurate, it blows my mind, the first page ends with "I can give you fully five minutes, Kuno. Then I must deliver my lecture on "The lasting effect of Burial on the dubstep scene in UK and beyond".

Gibson's Neuromancer which came some sixty years later was praised for anticipating the internet, but this is truly uncanny. Well, so far, my train journey ended at that point, the rest of it will have to wait until tomorrow.

woops

is not like other people

wasn't there in fact a Gibson story released as a computer document that deleted itself after being opened onceDisposable books - a great idea. Print with ink that fades within 5 minutes of exposure to the light.