Clinamenic

Binary & Tweed

That’s a lot of boots left to lick.come on, you've got 73 left!

That’s a lot of boots left to lick.come on, you've got 73 left!

you wait, you brood, you know futility intimatelyIt happens sometimes. Who are you talking to? What are you trying to say?? You have no idea, you can't answer.

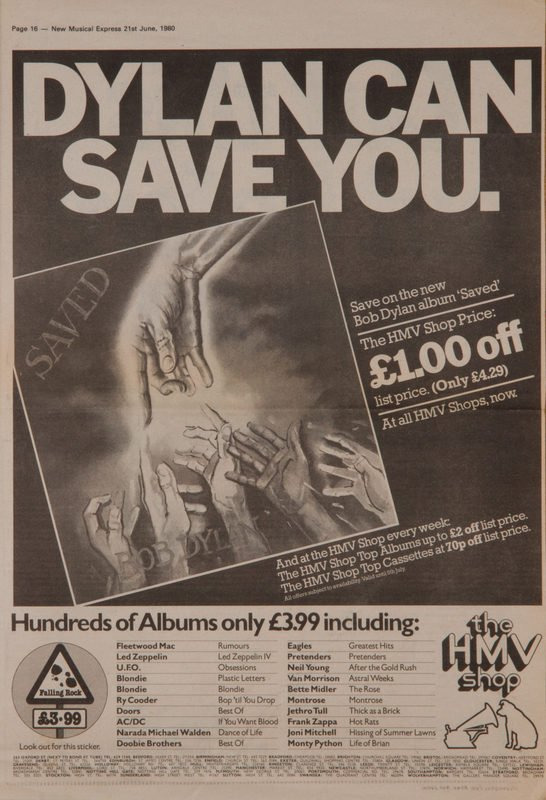

I think when my dad was a teen/young adult, he took the whole "Dylan goes Christian" phase pretty hard, it's all contaminated for him now.

Time's ability to redeem the trash of yesteryear captures my imagination, yes. I've always wondered the extent to which future generations will look back nostalgically on the mediocre mainstream of our time, the way we look back at, say, 60s and 70s pop songs.

“One has only to listen to the record albums that are now being revived as the hits, songs, and chansons from the twenties to be astonished at how little has changed in this whole sphere. As with fashion, the packaging changes; but the thing itself, a conventional language composed of signals to suit the conditioned reflexes of consumers, essentially remained the same… While it seems that such past fashions have a naive and awkward aspect in comparison with the current trend — that they are what the slang of American light music calls corny —this is due less to the substance of what is disseminated than to the time factor in abstracto, at most to the progressive perfecting of the machinery and of social-psychological control. The quality of being not yet quite so smart, which provokes smiles… is of the same nature as the idealizing nostalgia that clings to those same products today. The period’s comparative backwardness in the techniques of consumer culture is misinterpreted as though to mean it was closer to the origins, whereas in truth it was just as much organized to grab customers as it is in 1960. In fact, it is a paradox that anything at all changes within the sphere of a culture rationalized to suit industrial ideals; the principle of ratio itself, to the extent that it calculates cultural effects economically, remains the eternal invariant. That is why it is somewhat shocking whenever anything from the sector of the culture industry becomes old-fashioned.”

“It is perfectly self-evident that after thirty or forty years, after the absolute break, one cannot simply pick up where things were left off. The significant works of that epoch owed much of their power to the productive tension with a heterogeneous element: the tradition against which they rebelled. This was still a force confronting them, and it was precisely the most productive artists who had a great deal of that tradition within them. Much of the constraint that inspired those works was lost when the friction with this tradition disappeared. Freedom is complete, but threatens to become free-wheeling without its dialectical counterpart, whereas that counterpart cannot be maintained simply by an act of the will. Contemporary art must become conscious not only of its technical problems, but also of the conditions of its own existence, so that it does not become a mere rehash of the twenties, does not degrade into precisely what it refused to be: cultural property. Art’s social arena is no longer an advanced or perhaps even decayed liberalism, but rather a fully manipulated, calculated, and integrated society, the “administered world.” Whatever protest is made

against this in terms of artistic form — and it is no longer possible to conceive of an artistic form that is not a protest — itself becomes integrated into the universal planning it is attacking and bears the marks of this contradiction. Since their material has been emancipated and processed in every dimension nowadays, artworks evolve purely from their own formal laws, without any heterogeneous element, and so they tend to become all too shiny, tidy, and innocuous. In this sense, wallpaper swatches are the writing on the wall. It is precisely the discomfort caused by this that draws attention back to the twenties but without this nostalgic yearning being satisfied. Anybody who is sensitive to such things need only examine the titles of the innumerable books, paintings, and compositions of the past few years to have the sobering feeling of the secondhand. It is so unbearable because every work created nowadays makes its entrance —whether intentionally or not — as though it owed its existence to itself alone. The desire that proved fatal, namely, the absence of a work’s necessity to exist, gives way to the abstract consciousness of up-to-dateness. This ultimately reflects the absence of any political relevance. When it is completely transposed into the aesthetic domain, the concept of radicalness becomes an ideological distraction, a consolation for the real powerlessness of political subjects. […]

This surely means nothing less than that the foundation of art itself has been shaken, that an unrefracted relation to the aesthetic realm is no longer possible… However, because the world has survived its own downfall, it nonetheless needs art to write its unconscious his- tory. The authentic artists of the present are those in whose works the uttermost horror still quivers.”